Out & Back

Posted on Numéro Cinq: Reliable and Unreliable Narrators in Novels with Multiple Points of View — Rashmi Vaish

Rashmi Vaish

Rashmi Vaish

Introduction

Fictional reliability as a device of point of view is one of the most complex elements of craft. It relates to the ways in which an author causes the narrators or characters to interact with the fictional world and each other to present different perspectives or points of view to manipulate the reader’s experience of and response to the story.

Point of view in literature, according to David Jauss in Alone With All That Could Happen,

…refers to three not necessarily related things: the narrator’s person (first, second, or third), the narrative techniques he employs (omniscience, stream of consciousness, and so forth), and the locus of perception (the character whose perspective is presented, whether or not that character is narrating). Since there is no necessary connection between person, technique, and locus of perception, discussions of point of view in fiction almost inevitably read like relay races in which one definition passes off the baton to the next…(25)

The last element of point of view that Jauss speaks of, the locus of perception, is where I would pass the baton to fictional reliability. For this thesis I explore three novels with multiple points of view and discuss how the point of view complexes relate to reliability within each of them: Ironweed by William Kennedy, Dinner at the Homesick Restaurant by Anne Tyler, and The Sound and the Fury by William Faulkner.

First, a brief discussion of reliability. Wayne C. Booth in his book The Rhetoric of Fiction talks of reliability as a point of view narration concept relating to authorial distance:

In any reading experience, there is an implied dialogue among author, narrator, the other characters, and the reader. Each of the four can range, in relation to each of the others, from identification to complete opposition, on any axis of value, moral, intellectual, aesthetic, and even physical. (155)

For practical criticism probably the most important of these kinds of distance is that between the fallible or unreliable narrator and the implied author who carries the reader with him in judging the narrator. If the reason for discussing point of view is to find how it relates to literary effects, then surely the moral and intellectual qualities of the narrator are more important to our judgment than whether he is referred to as “I” or “he,” or whether he is privileged or limited. If he is discovered to be untrustworthy, then the total effect of the work he relays to us is transformed. (158)

He then goes on to define reliable and unreliable narrators:

For lack of better terms, I have called a narrator reliable when he speaks or acts in accordance with the norms of the work (which is to say the implied author’s norms), unreliable when he does not. (Booth 158)

Depending on the text, the narrators could be wholly reliable, wholly unreliable, or range somewhere along the spectrum—parts of their experience feel true and are in keeping with the novel world; others, though told with conviction, the reader knows are false. The reader knows this because the other characters in the narrative tell us so; the author tells us by depicting the world in opposition to the character. The reader sees clearly that the character is not perceiving the novel world accurately.

While the first-person mode of narration is what initially comes to mind when discussing reliability or unreliability as a device of point of view, “the most important unacknowledged narrators in modern fiction are the third-person ‘centers of consciousness’ through whom authors have filtered their narratives.” (Booth 153) These narrators provide a range of depictions of characters’ minds, from delving deep into the “complex mental experience” to the “sense-bound ‘camera eyes’” experience. Any kind of narration along this spectrum when used in conjunction with other craft devices leads to reliability or unreliability.

In novels with single points of view, where there is one narrating consciousness through whose eyes the reader must see the novel world, first-person or third, there is a pressure on the narrating consciousness to provide the bulk of the significant detail of the story. We get back story, history and setting through devices like memory, perception and interior monologue, and other characters’ opinions of the narrator through direct dialogue in present action or memory scene. In novels with multiple points of view, however, this pressure is alleviated. We get a variety of views on the novel world, each perspective coloring the same events in different hues. One perspective is set up against the other and so we as readers discover for ourselves which narration holds the most reliability or unreliability.

Ironweed

First published in 1983, Ironweed by William Kennedy won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1984. The book is the third in Kennedy’s Albany series of novels, though stands alone as a single work. Francis Phelan, a former major league baseball player, is a vagrant drunk who has returned to his hometown of Albany after 22 years. He fled home after dropping his infant son Gerald and killing him. Prior to that he had run away for a while after killing a man during a transit strike and was on the road extensively during his baseball career. The novel, which takes place over two days and nights, opens with Francis in St Agnes Cemetery, where his family and relatives are buried. He and another bum friend of two weeks, Rudy, have picked up a job digging graves because Francis needs to work off some legal fees. In the cemetery, Gerald’s ghost imposes a silent act of will on Francis indicating that he needs to “perform his final acts of expiation for abandoning the family.” (19)

William Kennedy

William Kennedy

Francis isn’t consciously aware of this; in the cemetery he sees no ghosts, hears no voices. It is Halloween and it is only when Francis leaves the cemetery that he begins to see ghosts of the people he has killed. During the course of the night he meets up with Helen Archer, a hobo with whom he has had a relationship for nine years. Helen, who used to be a musician from a good family and is now dying of a tumor, is the other point of view consciousness of the novel. That night Helen is robbed of her purse.

The following day Francis gets a job with a man who hauls junk and while on their rounds he enters his old neighborhood, which makes him remember his own home, his neighbors, parts of his childhood and young adult years. He decides to buy a turkey with his day’s earnings and visit his family, with whom he ends up spending the evening. While there, he finally faces his wife, Annie, who welcomes him into their home. She is surprised to see him but bears no acrimony towards him. He apologizes to her, telling her that he still loves them but expects nothing. He meets his grandson, his son and daughter, and Annie cooks the turkey for the evening meal, for which he stays. He bathes, wears a clean suit that used to belong to him, and hands his present rags over to be discarded. Annie acknowledges that his returning, visiting Gerald’s grave, and coming to see her is significant. She asks if he wants to stay, he refuses, but she leaves the possibility open. The family has dinner together.

Later, he goes to find Helen, who in the meantime has checked into a hotel and is preparing to die. He leaves some money for her at the desk and meets up with Rudy. Soon after, however, the hobo jungle is raided, and Rudy is seriously injured in the violence. Francis takes him to the hospital, where Rudy dies. He returns to the hotel and finds Helen dead. He gets back on a train out of Albany to flee the police once again, but the ghost of Strawberry Bill tells him the police are not looking for him and that the house, the attic with the cot he saw earlier, is the best place for him to be. He projects into the future, thinks about possibly even moving into his grandson’s room when the time is right. In the end he finds peace in Anneie’s forgiveness. His spiritual burden is lifted, his deeds over the two days a fulfilling of the expiation that Gerald’s ghost imposed on him.

The Author as God Voice/Omniscient Narrator

While the bulk of the novel occurs in Francis Phelan’s point of view, with Helen Archer a secondary point of view character, the first chapter of the novel has a distinctly different perspective. This voice, the authorial voice or reliable omniscient third person narrator, sets up Francis’ world in context to the Catholic afterlife with the literal introduction of the dead speaking and interacting with the world right in the beginning of the novel—his mother twitches in her grave and his father lights his pipe (1). The author gives the reader a great deal of mobility in this section in terms of distance, taking the reader close into Francis’ thoughts and far out into the spirit world that Francis is not yet aware of. The modes of interiority are used not only for Francis, but for the ghosts around Francis in the cemetery as well. The ghosts in this section don’t just speak amongst themselves; in a presaging of what is to come in the novel, they speak to Francis as well, like Louis (Daddy Big) Dugan, who tells Francis that his son Billy “saved my life.” (5) Only, at this point Francis doesn’t hear or see any ghosts yet.

The dramatic action begins with Francis riding in a truck through the cemetery in Albany where his family is buried. The narrator/observer moves with Francis through the graveyard, giving us back story and character setup for Francis as well:

Francis knew how to drink. He drank all the time and he did not vomit. He drank anything that contained alcohol, anything, and he could always walk, and he could talk as well as any man alive about what was on his mind…He’d stopped drinking because he’d run out of money, and that coincided with Helen not feeling all that terrific and Francis wanting to take care of her. Also he had wanted to be sober when he went to court for registering twenty-one times to vote. (6)

The most important piece of setup in this chapter, the event that sets the rest of the novel in motion, comes when Francis goes to his infant son Gerald’s grave. The authorial voice indicates that this is an important moment by describing Francis’ dead father Michael signaling to “his neighbors that an act of regeneration seemed to be in process” (16).

A brief shift into Rudy’s mind also occurs before Francis arrives at Gerald’s grave, giving us multiple perspectives on the significance of the action unfolding:

Rudy followed his pal at a respectful distance, aware that some event of moment was taking place. Hangdog, he observed. (17)

At this point the narration speaks from Gerald’s perspective as ghost, though Francis remains unaware:

Gerald, through an act of silent will, imposed on his father the pressing obligation to perform his final acts of expiation for the family… You will not know what these acts are until you perform them… when these final acts are complete, you will stop trying to die because of me. (19)

The unadorned declarative text that lays out his immediate future path grounds his character in the novel world. The authorial voice gives the reader the guidepost to understanding Francis and his actions to come. This chapter functions as the closest example of a reliable, omniscient narrator who is the only one in the novel world fully aware of everything surrounding Francis, including the afterlife and the task that Francis must perform, which he is unaware of, but which the reader knows.

Read the rest at Numéro Cinq Magazine. Click here.

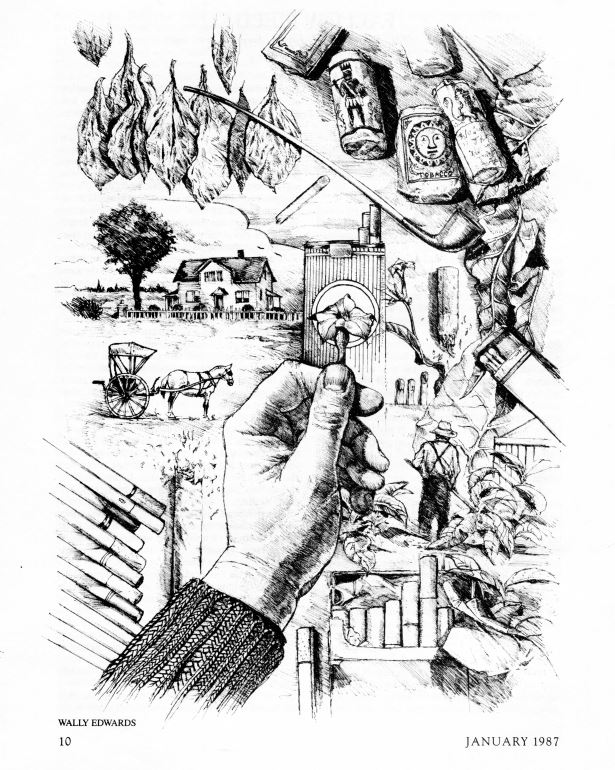

Fallow Fields

I was rummaging in boxes on the farm in Ontario recently I found an old issue of The Canadian Forum with my essay “Fallow Fields” (The Canadian Forum, January 1987). My father had died in 1984, leaving the family tobacco farm to my mother in a troubled time. We were havering between different imagined futures for the land, much as we are today. I wrote this essay in an effort to think through the situation for myself. It made a splash. Peter Gzowski, Captain Canada, interviewed me on CBC Morningside.

Some of the text is dated now, that moment in economic and technological history is long gone. But the bulk of the essay about the history of the farm and tobacco growing is golden in capturing the times. Here’s an excerpt:

The farm I grew up on has been in the family since 1900, when my grandfather bought it (155 acres less five when the Lake Erie & Northern Railway expropriated a right-of-way through the property in 1914) for $7,000. About 40 acres of this was mixed woods — maple, beech, and oak — with a swamp and springs that flow eventually into Lake Erie 20 miles away. There were some damp, low spots, which were fenced for pasture then and planted with corn or soybeans now, and some persistently sterile and yellow hilltops (“sandy knolls” my father called them) that still require extra fertilizer and careful erosion control. The rest was relatively fertile sandy loam, good for growing almost anything; ideal, it turned out later, for tobacco.

Besides the farm buildings, a hired man’s house, and a smaller house for summer help, there was a large Georgian fieldstone farmhouse, beautiful, imposing, but hard to heat, built by the farm’s original owner, a Dr. Duncombe (brother of Dr. Charles Duncombe, who raised the flag of rebellion in Scotland in 1837). I have looked the place up in an 1877 county atlas: there are three orchards marked, along with a small graveyard.

Whether those orchards survived, or whether my grandfather had a special predilection — his Loyalist forbears settled for a while on the Niagara Peninsula — he started out as a fruit grower. But not just one fruit, or one variety of fruit. This was an era of agriculture before mechanization, agribusiness, monocultures, and, for that matter, tobacco. In the field next to the house, my grandfather grew black currents (picked in 11-quart baskets and shipped by the L.E.&N. to Brantford or taken by car to Norwich and Kitchener) and gooseberries. There was a stile across the railway fence and then a patch of raspberries. South of the raspberries we had a five-acre apple orchard (that’s where the kiln yard is now; one lone apple tree is left, dropping its scant, wormy fruit on the cureman’s shack year after year). The apples were old-fashioned varieties, mostly out of favour now because they don’t store or ship well: Greens, Northern Spies, Snow Apples, and Tallman Sweets (packed in barrels and sent away by rail). North of the barn there were a couple of acres of cherries and about the same in pears (my grandfather tried peaches first, but they were frozen out) — again, what is striking is the variety: Kiefers, hard as bullets when picked; Bartletts for canning; Clap Favourites, a dessert pear that started to spoil practically as soon as it came from the tree.

But the farm’s main income came from strawberries, which my grandfather grew in eight- to 12-acre patches, moving the patch every couple of years as the plants went past their peak. Strawberry harvest was the busiest time on the farm, with as many as 60 people; whole families of Iroquois Indians —Generals, Sowdens and Jacobs — came from the nearby Six Nations Reserve to live in rough duplex shacks (they had bunks inside and a cook stove on the porch) my grandfather provided while the season lasted. (There is a shade of irony in the thought that these Iroquois were the same fierce warriors who exterminated the first Ontario tobacco growers, the Neutrals and Petuns, while Canada was still a French colony.) The berries were taken on flatracks to Waterford and loaded onto Michigan Central refrigerator cars bound for Montreal or Detroit. My grandfather did his selling by telephone, anxiously calling between the two cities for the highest price.

By modern standards it was a very mixed farm and quite self-sufficient. Behind the house there was a garden, a chicken run, a hog yard, and along, red hog barn; once a year my grandfather killed a pig and made sausages and lard and cured hams in the stone smokehouse. He kept cows, too, six or seven of them for milking, though he never liked them and my grandmother refused to let him build a silo or get too deeply into the livestock side of the business. During the summer the cows were pastured at the edge of the woods on the north side of the property. Twice a day my father or my aunt walked to the head of the pasture lane to shout, “Cow-Boss! Cow-Boss!” and the cows would amble home and into their stalls for milking. Some of the milk was used on the farm, some was sold in large metal cans picked up every day by a dairy truck.

There was a gabled drive shed for storing machinery,with a weather vane and a circular glass window in the gable, and a large two-storey barn with stables for cows and horses on the ground floor, and a grainary and hay loft above. Hay, oats, rye, wheat, and turnips were grown on the farm and stored in the barn to feed the animals (some of the grain was ground into grist at a nearby mill; my aunt split the turnips with a hand-turned cutter), and, naturally, we did not need to buy commercial fertilizers. A windmill pumped water to the house and barn. For labour my grandfather depended mainly on a permanent hired man (and his wife) who worked on the farm in return for a rent-free house, firewood cut in the woods, milk, use of a driving horse, land for a garden, and wages that amounted to about $400 to $600 a year (I’m talking about, roughly, the time of the First World War — the troops were getting $1.10 a day). During the summer, my grandfather would often employ a temporary hired man as well. There was a second, smaller tenant house for him and his family and, of course, he also got the free milk, firewood and garden.

You can download and read the rest of the essay here.

And here is a selection of earlier blog posts about the farm (lots of photos).

dg’s personal blog archive @ Numéro Cinq

I’m reviving my Numéro Cinq Out & Back blog on my own site. It inhibited me writing on the magazine site, feeling a bit like I was forcing it to limp along, addressing all those readers who were loyal to the magazine without necessarily having a personal connection with me, also not wanting ride on the magazine’s coattails. And perhaps just wanting a fresh start of sorts, without the magazine.

To that end, and to begin with, here is a link to all my old blog posts at NC (or click the logo above). This will give me a base for an ongoing conversation, mostly with myself.

(Note: I shall continue my habit of switching between the first and third person because it’s fun.)